article Monuments of Meaning

Monuments of Meaning

Writer and artist Phineas Harper looks

at art that goes against the grain of capitalism

and commodification, exploring alternative pursuits

that prioritise personal and planetary well-being over GDP.

at art that goes against the grain of capitalism

and commodification, exploring alternative pursuits

that prioritise personal and planetary well-being over GDP.

Writer and artist Phineas Harper looks

at art that goes against the grain of capitalism

and commodification, exploring alternative pursuits

that prioritise personal and planetary well-being over GDP.

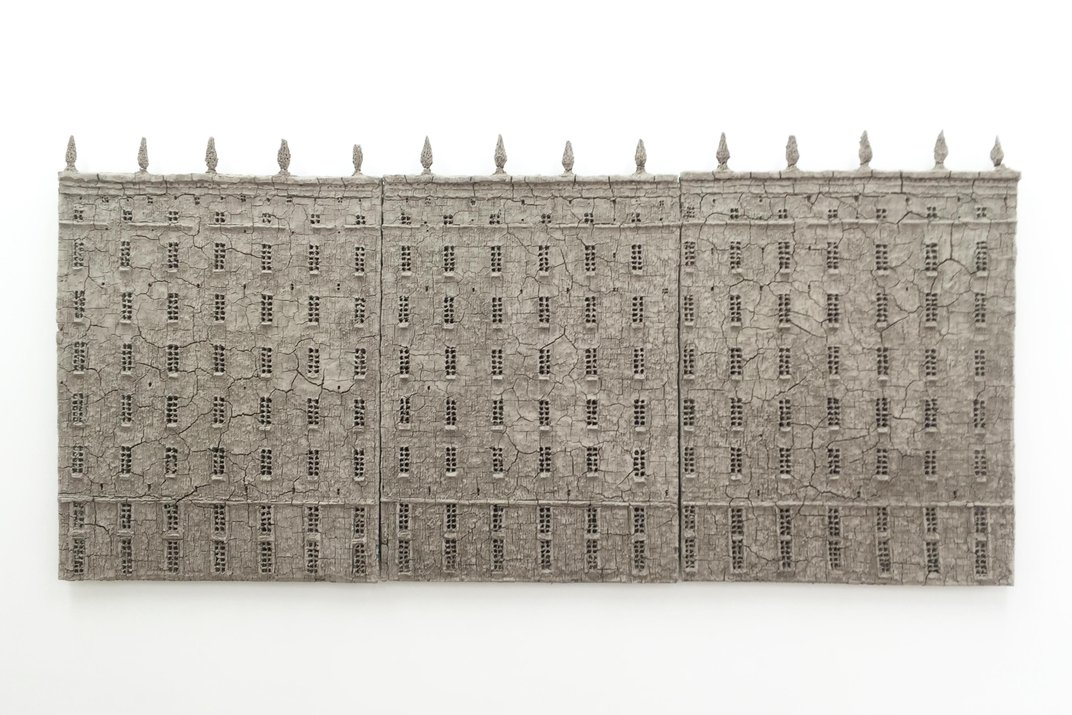

In 2014, Russian artist and architect Alexander Brodsky made a series of wall-mounted sculptures depicting the facades of imagined imposing buildings with windows and cornices scratched into slabs of unfired grey clay. Gradually cracking and flaking as they slowly dry where hung, eventually the sculptures will crumble. A jibe at the fallacy of permanence in architecture? A note on mortality? Or perhaps a cantankerous challenge to the Art World and the economics of how contemporary art is bought, sold and speculated upon.

Art, often, is seen as an asset; a thing we buy and own as an investment which can be sold on in the future (perhaps at a profit). But Brodsky’s fragile facades have no future; they are on a one-way journey to dust. Their disappearing existence has a built-in time limit making their economic value under the conventional calculus of late capitalism ambiguous. Many think that ecological art is about materials – sculptures carved from carbon-sequestering wood rather than cast in bronze at energy-guzzling foundries for example are, in a way, one answer to the question of sustainable art production. But the bigger and infinitely more exciting opportunity is to explore art’s power as a component of the global economy driving climate breakdown, and to imagine what role it can play in shifting and provoking change.

Since the 1930s, economic expansion expressed in a growing Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has been our main method of measuring national success. However, GDP growth has little bearing on true social health. When economists say “Britain is the sixth richest country in the world” they don’t mean its citizens have the sixth best access to resources enabling them to live healthy, long and fulfilling lives, they merely mean the tradeable value of all the products and services produced in the UK adds up to more than in other states.

Art, often, is seen as an asset; a thing we buy and own as an investment which can be sold on in the future (perhaps at a profit). But Brodsky’s fragile facades have no future; they are on a one-way journey to dust. Their disappearing existence has a built-in time limit making their economic value under the conventional calculus of late capitalism ambiguous. Many think that ecological art is about materials – sculptures carved from carbon-sequestering wood rather than cast in bronze at energy-guzzling foundries for example are, in a way, one answer to the question of sustainable art production. But the bigger and infinitely more exciting opportunity is to explore art’s power as a component of the global economy driving climate breakdown, and to imagine what role it can play in shifting and provoking change.

Since the 1930s, economic expansion expressed in a growing Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has been our main method of measuring national success. However, GDP growth has little bearing on true social health. When economists say “Britain is the sixth richest country in the world” they don’t mean its citizens have the sixth best access to resources enabling them to live healthy, long and fulfilling lives, they merely mean the tradeable value of all the products and services produced in the UK adds up to more than in other states.

Alexander Brodsky, Untitled, 2014, unfired clay, 84 x 76 cm. Courtesy of the Artist and Betts Project.

In fact, as has become starkly clear in recent decades, GDP growth is driving increasing energy consumption, extraction of natural resources, and greenhouse gas emissions, all accelerating environmental collapse. Redesigning the global economy to prioritise culture, well-being, and ecology over the pursuit of GDP growth, is now a fundamental challenge facing every corner of society including the Art World. How art should adapt and learn from degrowth and circular economics, is an urgent and exhilarating conundrum.

In 1986, Esther Shalev-Gerz and Jochen Gerz made their own disappearing artwork. Their Monument Against Fascism in Hamburg-Harburg began as a 12-metre steel column upon which residents could carve messages of rage, fury, love and loss into the lead-faced exterior. As each section became saturated with writing, the column was incrementally lowered into the ground until, in 1993, the artwork disappeared entirely. As stated on the invitation panel, “In the long run, it is only we ourselves who can stand up against injustice”.

Today the monument is effectively gone, buried along with eight years of outpoured grief. Yet its self-destruction – the very fact that it doesn’t linger on like the statues of dead slave owners and military generals which litter our public realm – makes it all the more meaningful. Clearly, not all art needs to physically endure as a potentially tradeable commodity to wield value. Untangling art from the logic of consumerism in a post-growth economy could be a rich and expansive challenge for ambitious artists and curators to explore.

In 1986, Esther Shalev-Gerz and Jochen Gerz made their own disappearing artwork. Their Monument Against Fascism in Hamburg-Harburg began as a 12-metre steel column upon which residents could carve messages of rage, fury, love and loss into the lead-faced exterior. As each section became saturated with writing, the column was incrementally lowered into the ground until, in 1993, the artwork disappeared entirely. As stated on the invitation panel, “In the long run, it is only we ourselves who can stand up against injustice”.

Today the monument is effectively gone, buried along with eight years of outpoured grief. Yet its self-destruction – the very fact that it doesn’t linger on like the statues of dead slave owners and military generals which litter our public realm – makes it all the more meaningful. Clearly, not all art needs to physically endure as a potentially tradeable commodity to wield value. Untangling art from the logic of consumerism in a post-growth economy could be a rich and expansive challenge for ambitious artists and curators to explore.

Esther Shalev-Gerz and Jochen Gerz, Monument against Fascism, 1986, Permanent installation, Hambourg-Harbourg, Germany, installation view, 1986, © Atelier Shalev-Gerz.

By contrast, the visible rise and fall of Non Fungible Tokens (NFTs) reveals the cultural dead end that awaits art which centres its purpose entirely on ownership and trade. The 10,000 “programmatically generated” cartoons which make up the Bored Ape Yacht Club NFT collection, for example, have contributed gainfully to GDP growth, but are otherwise phenomenally banal; their derivative design an emaciated shadow of Jamie Hewlett’s artwork for the fictional pop band, Gorillaz. The Apes have no cultural, aesthetic or philosophical value – merely a cash value for how much of a given cryptocurrency they retail at – nothing more.

The opposite of NFTs are tattoos. For me, these indelible marks on my skin carry reminders of my roots and values but they are also totally worthless. Tattoos are economically bizarre investments because as soon as you've bought one, you can never sell it. No matter how famous the artist or how elaborate and costly the piece, a tattoo, once drawn, has no resale potential. If an NFT’s value is entirely about its price, a tattoo’s value is entirely about its meaning.

It’s not just tattoos and Brodsky’s crumbling facades that refuse to play nicely with the conventional rules of economic exchange. In fact, the value of many rewarding activities are impossible to recognise through the limited framework of GDP. Faith, prayer, meditation, gardening, gossip, amateur sports, long walks in the countryside, many hobbies, spending time with friends and family, romance, sexual pleasure and play are all examples of things humans pursue and find deeply nourishing which produce little or no economic output but are at the core of a good life nonetheless. A Britain in which everyone worked several hours fewer per week but spent more time appreciating art, experiencing nature and getting laid instead would certainly have a smaller GDP, but its citizens would undoubtedly be happier and healthier than they are today.

Impossible to sustain in the long term and harmful in the short, the pursuit of perpetual GDP growth will eventually come to an end. By testing and embodying forms of value that transcend the logic of GDP entirely, art and artists cannot just be part of, but help define and shape, the truly sustainable ecological economy of tomorrow.

The opposite of NFTs are tattoos. For me, these indelible marks on my skin carry reminders of my roots and values but they are also totally worthless. Tattoos are economically bizarre investments because as soon as you've bought one, you can never sell it. No matter how famous the artist or how elaborate and costly the piece, a tattoo, once drawn, has no resale potential. If an NFT’s value is entirely about its price, a tattoo’s value is entirely about its meaning.

It’s not just tattoos and Brodsky’s crumbling facades that refuse to play nicely with the conventional rules of economic exchange. In fact, the value of many rewarding activities are impossible to recognise through the limited framework of GDP. Faith, prayer, meditation, gardening, gossip, amateur sports, long walks in the countryside, many hobbies, spending time with friends and family, romance, sexual pleasure and play are all examples of things humans pursue and find deeply nourishing which produce little or no economic output but are at the core of a good life nonetheless. A Britain in which everyone worked several hours fewer per week but spent more time appreciating art, experiencing nature and getting laid instead would certainly have a smaller GDP, but its citizens would undoubtedly be happier and healthier than they are today.

Impossible to sustain in the long term and harmful in the short, the pursuit of perpetual GDP growth will eventually come to an end. By testing and embodying forms of value that transcend the logic of GDP entirely, art and artists cannot just be part of, but help define and shape, the truly sustainable ecological economy of tomorrow.

Phineas Harper is the former chief executive of Open City and Open House Worldwide and a regular columnist at Dezeen and the Guardian, exploring the intersection of architecture and politics. Alongside writing, their work spans kinetic sculpture, film and printmaking.

Explore other articles from Artiq Annual Volume 2 or read the full annual online here.

Explore other articles from Artiq Annual Volume 2 or read the full annual online here.