article What businesses can learn from the psychology of creativity

What businesses can learn from the psychology of creativity

On Creativity

by George Bird

by George Bird

On Creativity

by George Bird

When creativity is brought up, our minds often jump to scenes of great artists and musicians, Da Vinci in his Florentine studio, or Picasso scribbling on napkins at restaurants, Mozart composing by candlelight or The Beatles working out another number one record. Beyond these we might start to think of great scientists and inventors such as Tesla and Edison tinkering away in labs and Marie Curie working towards either of her Nobel Prizes. Modern examples include Sirs Jony Ive, James Dyson, or Tim Berners-Lee.

Creativity in this sense is often held as something almost otherworldly and unknowable, creatives are thought of as just ‘having it’. But creativity is not just massive ideas, world famous artworks and music or new and unique industry defining products. Creativity appears in all areas of our lives, no matter the scale - this is reflected in the approach of modern psychology to the phenomenon of creativity. An emphasis on the importance of creativity is also growing within non-traditional ‘creative’ sectors. Increasingly, the ability to understand and foster creativity whatever the space is a crucial role of business leaders and teams.

Creativity is now accepted as a major part of who we are and how we work, but psychology hasn’t always given it the attention it deserves. In 1950 as President of the American Psychological Association, J. P. Guildford, highlighted that only 0.2% of the current psychological research was dealing with creativity and creative impulses and challenged the field to remedy this lack of research into creativity. And psychologists responded. Over the next years and decades, Guildford’s call to action spurred a more enthusiastic move into creativity research which continues today. Guildford himself expanded the research base with his theory of convergent and divergent thinking, now part of the common Myers-Briggs test. This structure categorises thoughts as convergent, in which thinking focuses towards one efficient solution to a problem, or divergent, where thoughts expand outward from the solution and involve multiple novel or unconventional solutions to the problem. Further research largely focuses on the divergent type thinking in which creativity is most apparent.

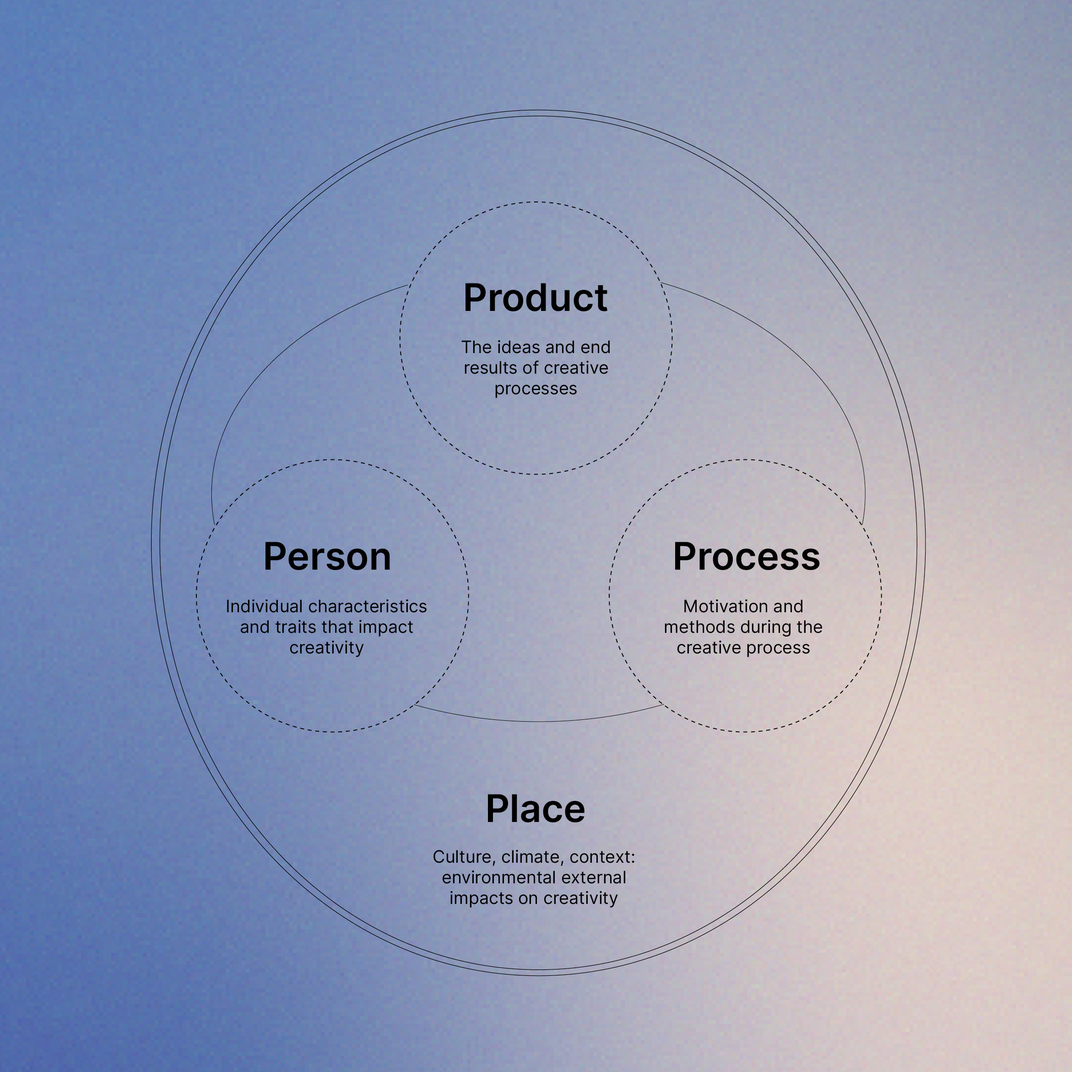

A further analysis of the research base in the 1960s, defined four main groupings of psychological research, known as the four Ps. These are ‘persons’ focusing on the individual traits and personalities that affect creativity, ‘process’ focusing on the motivation, and thinking during the creative process, ‘press’ explained as the external environmental factors affecting creative outcomes and ‘product’ studying the ideas and end results of creative processes. Throughout the 1960s, the groundwork was laid for further development in the field. Many of the common measures still in use today were created and began to see widespread use.

Creativity in this sense is often held as something almost otherworldly and unknowable, creatives are thought of as just ‘having it’. But creativity is not just massive ideas, world famous artworks and music or new and unique industry defining products. Creativity appears in all areas of our lives, no matter the scale - this is reflected in the approach of modern psychology to the phenomenon of creativity. An emphasis on the importance of creativity is also growing within non-traditional ‘creative’ sectors. Increasingly, the ability to understand and foster creativity whatever the space is a crucial role of business leaders and teams.

Creativity is now accepted as a major part of who we are and how we work, but psychology hasn’t always given it the attention it deserves. In 1950 as President of the American Psychological Association, J. P. Guildford, highlighted that only 0.2% of the current psychological research was dealing with creativity and creative impulses and challenged the field to remedy this lack of research into creativity. And psychologists responded. Over the next years and decades, Guildford’s call to action spurred a more enthusiastic move into creativity research which continues today. Guildford himself expanded the research base with his theory of convergent and divergent thinking, now part of the common Myers-Briggs test. This structure categorises thoughts as convergent, in which thinking focuses towards one efficient solution to a problem, or divergent, where thoughts expand outward from the solution and involve multiple novel or unconventional solutions to the problem. Further research largely focuses on the divergent type thinking in which creativity is most apparent.

A further analysis of the research base in the 1960s, defined four main groupings of psychological research, known as the four Ps. These are ‘persons’ focusing on the individual traits and personalities that affect creativity, ‘process’ focusing on the motivation, and thinking during the creative process, ‘press’ explained as the external environmental factors affecting creative outcomes and ‘product’ studying the ideas and end results of creative processes. Throughout the 1960s, the groundwork was laid for further development in the field. Many of the common measures still in use today were created and began to see widespread use.

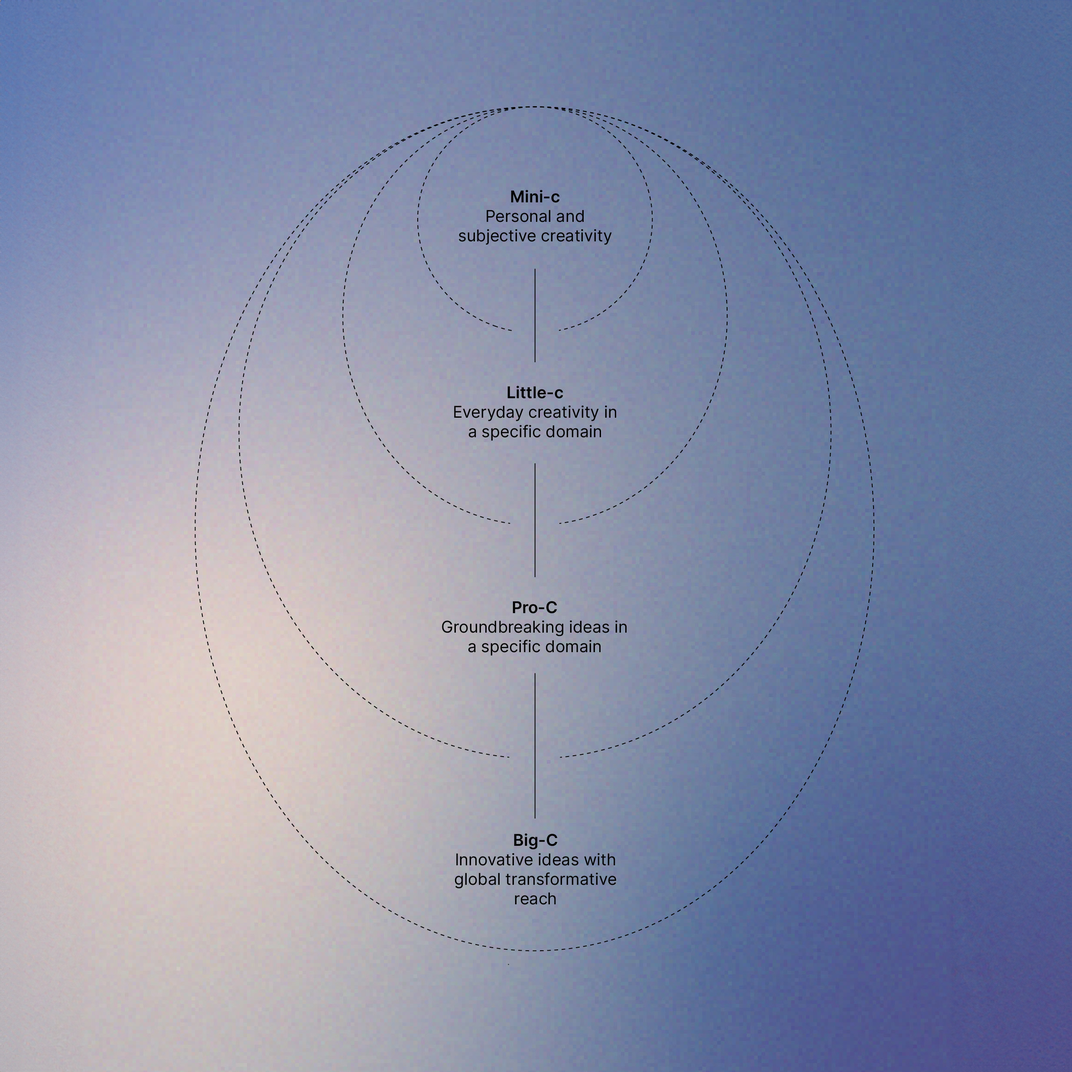

Kaufman and Beghetto's four-C Model for creativity.

Psychology also began to take an increasingly interdisciplinary approach to research, drawing on sociological research and research into education to allow more nuanced and diverse approaches to appear in the following decades. This diversification in the research is demonstrated in a recent literature review from 2021, identifying 12 major areas of creativity research along with 36 key trends from recent years in comparison to the 4 of 1960. Psychology papers relating to creativity are now being published at a rate of around 3000 per year with the majority relating to creativity within organisations and teams, the social psychology of creativity, creative industries, and cities and idea generation. Other major areas focus on the neuroscience of creativity as well as specific creative industries and therapies.

Traditionally, the dominant psychological categorisation of creative thought has split creativity into two ‘types’, big and little C. However, this categorisation of creativity can seem limited in its scope. Against the general trend of psychology to minimise theoretical structures Kaufman and Beghetto have proposed a more developed model, the four-C model of creativity which expands upon the previous models with the inclusion of Pro-c and Mini-c creativity. These 4 levels present creativity as a continuous scale in order of Mini-c, Little-c, Pro-C and Big-C. Big-C creativity refers to large-scale ideas with a global transformative reach. These ideas are characterised by the significant impact they have on our world even outside of their specific domains. They must also be new and novel and often completely shift the approach to a field, creating an enduring and lasting impact. Big-C ideas commonly come from eminent figures, well respected within their fields, such as those used in the introduction.

The first of Kaufman and Beghetto’s additional levels, Pro-C creativity comes between Big and Little-c and represents ideas that are groundbreaking within their specific domain but do not go beyond to a global reach. These ideas come from professionals within their fields who may not have reached the top eminent level. These individuals include doctors and professors, professional designers or high-level engineers. Often overlooked and underappreciated in creative settings, Little-c refers to the everyday creativity that we all demonstrate, or creativity that happens within a specific domain and is therefore not as far reaching and transformative as Pro or Big-C. Little-c ideas are no less or more creative than Big-C, but have a different level of impact, and are often more domain specific. And finally, Mini-c, also known as subjective creativity, represents ideas that are personally novel and meaningful. These ideas or insights most often occur in individuals when they’re learning or experiencing things for the first time. While this structure allows us to categorise creative thoughts, it’s important not to think of these levels as a ranking. For every Big-C idea, there are layers of mini, little and pro-C ideas providing a base upon which these larger world- changing ideas can be launched.

Traditionally, the dominant psychological categorisation of creative thought has split creativity into two ‘types’, big and little C. However, this categorisation of creativity can seem limited in its scope. Against the general trend of psychology to minimise theoretical structures Kaufman and Beghetto have proposed a more developed model, the four-C model of creativity which expands upon the previous models with the inclusion of Pro-c and Mini-c creativity. These 4 levels present creativity as a continuous scale in order of Mini-c, Little-c, Pro-C and Big-C. Big-C creativity refers to large-scale ideas with a global transformative reach. These ideas are characterised by the significant impact they have on our world even outside of their specific domains. They must also be new and novel and often completely shift the approach to a field, creating an enduring and lasting impact. Big-C ideas commonly come from eminent figures, well respected within their fields, such as those used in the introduction.

The first of Kaufman and Beghetto’s additional levels, Pro-C creativity comes between Big and Little-c and represents ideas that are groundbreaking within their specific domain but do not go beyond to a global reach. These ideas come from professionals within their fields who may not have reached the top eminent level. These individuals include doctors and professors, professional designers or high-level engineers. Often overlooked and underappreciated in creative settings, Little-c refers to the everyday creativity that we all demonstrate, or creativity that happens within a specific domain and is therefore not as far reaching and transformative as Pro or Big-C. Little-c ideas are no less or more creative than Big-C, but have a different level of impact, and are often more domain specific. And finally, Mini-c, also known as subjective creativity, represents ideas that are personally novel and meaningful. These ideas or insights most often occur in individuals when they’re learning or experiencing things for the first time. While this structure allows us to categorise creative thoughts, it’s important not to think of these levels as a ranking. For every Big-C idea, there are layers of mini, little and pro-C ideas providing a base upon which these larger world- changing ideas can be launched.

James Rhodes' concept of the four P's of creativity.

While there’s a mass of research work available, businesses without a psychology background often struggle to find ways to develop new practices that could make use of these findings. A general understanding of some of the core ideas can start to bridge this gap. The most important factor in fostering creativity is an effective working environment. Here we highlight some small key ways to foster creativity within the workplace drawing on some of the psychological structures discussed previously. The first method of fostering creativity is recognising it. Returning to the four C’s structure, the ability to recognise and encourage creativity across the four levels will develop a more secure space in which ideas can grow. It’s important to reward and acknowledge the importance of ideas across the spectrum of impact rather than focusing too heavily on Pro and Big-C and disregarding mini and little-C.

Another key way is to allow space for creativity to happen. A rigid workplace without space for failure or autonomy will stifle creativity and create a focus on more convergent ways of thinking. While this may get results, it doesn’t leave space for other more creative or innovative solutions to be found. By clearly defining goals but providing low pressure spaces for ideas to be explored from multiple angles, more creative solutions can be developed using divergent thinking patterns. This is turn may lead to some surprising results. This further feeds into the need for unconventional thinking to be encouraged, and for failure to be viewed as a learning opportunity rather than a dead end. An individual or team who can be agile and respond to failure as a lesson can more easily use it to adapt and find novel solutions.

A final way of bringing creativity more into the workspace is actively setting aside time for it to happen. Providing time explicitly for teams to mix between themselves and with other teams will allow people the space to explore ideas that they may not otherwise have time for, and diversify the solutions to problems. By giving teams space to mix, individuals can often provide novel solutions by seeing problems in a new way, or by breaking out of established thinking styles that may have set in.

Establishing these key practices in the workplace should foster a new relationship to creativity and generate more diverse solutions to problems that businesses are likely to face. Creativity in this sense leads to more creativity. By providing the first stepping stones in fostering creative practices, creativity can develop as a new habit for many teams and businesses.

Another key way is to allow space for creativity to happen. A rigid workplace without space for failure or autonomy will stifle creativity and create a focus on more convergent ways of thinking. While this may get results, it doesn’t leave space for other more creative or innovative solutions to be found. By clearly defining goals but providing low pressure spaces for ideas to be explored from multiple angles, more creative solutions can be developed using divergent thinking patterns. This is turn may lead to some surprising results. This further feeds into the need for unconventional thinking to be encouraged, and for failure to be viewed as a learning opportunity rather than a dead end. An individual or team who can be agile and respond to failure as a lesson can more easily use it to adapt and find novel solutions.

A final way of bringing creativity more into the workspace is actively setting aside time for it to happen. Providing time explicitly for teams to mix between themselves and with other teams will allow people the space to explore ideas that they may not otherwise have time for, and diversify the solutions to problems. By giving teams space to mix, individuals can often provide novel solutions by seeing problems in a new way, or by breaking out of established thinking styles that may have set in.

Establishing these key practices in the workplace should foster a new relationship to creativity and generate more diverse solutions to problems that businesses are likely to face. Creativity in this sense leads to more creativity. By providing the first stepping stones in fostering creative practices, creativity can develop as a new habit for many teams and businesses.

George Bird is a recent graduate from MSc Psychology of Art, Neuroaesthetics and Creativity at Goldsmiths, the first postgraduate programme in the world for the scientific study of aesthetics and creativity.

Explore other articles from Artiq Annual Volume 2 or read the full annual online here.

Explore other articles from Artiq Annual Volume 2 or read the full annual online here.