article Queer Frontiers presents:

Louise Benton

Queer Frontiers presents:

Louise Benton

In conversation with Louise Benton

about how her work investigates collective

experiences unique to femininity, specifically

subjects which carry a stigma of shame.

about how her work investigates collective

experiences unique to femininity, specifically

subjects which carry a stigma of shame.

In conversation with Louise Benton

about how her work investigates collective

experiences unique to femininity, specifically

subjects which carry a stigma of shame.

Louise Benton is a London-based artist and illustrator with degrees in Fine and History of Art. Louise’s work explores representations of the female figure, particularly within modern life. She seeks to investigate collective experiences unique to femininity, subjects which carry a stigma of shame.

Louise is one of the exhibiting artists of this year’s Queer Frontiers: Queer Myths, Queer Futures and we had the privilege to ask her about her practice and the limited edition print created for the exhibition.

Louise is one of the exhibiting artists of this year’s Queer Frontiers: Queer Myths, Queer Futures and we had the privilege to ask her about her practice and the limited edition print created for the exhibition.

Artiq In your practice, you use the visual language of Catholicism to tell contemporary stories of sexuality and pleasure. How do you find the balance between such distant worlds?

Louise I think Catholic visual language is so specifically tailored to show pleasure, to the point that even gruesome images of saints being disembowelled or grilled show them looking thrilled about it.

Traditionally, the aim is to persuade the viewer that they too can undergo any extreme of pain and still emerge in bliss if they have sufficient faith. There's a crossover between the religious and the sexual that I find to be a really rich and human mode of representation, that I’d like to harness and give contemporary stories that same power.

Louise I think Catholic visual language is so specifically tailored to show pleasure, to the point that even gruesome images of saints being disembowelled or grilled show them looking thrilled about it.

Traditionally, the aim is to persuade the viewer that they too can undergo any extreme of pain and still emerge in bliss if they have sufficient faith. There's a crossover between the religious and the sexual that I find to be a really rich and human mode of representation, that I’d like to harness and give contemporary stories that same power.

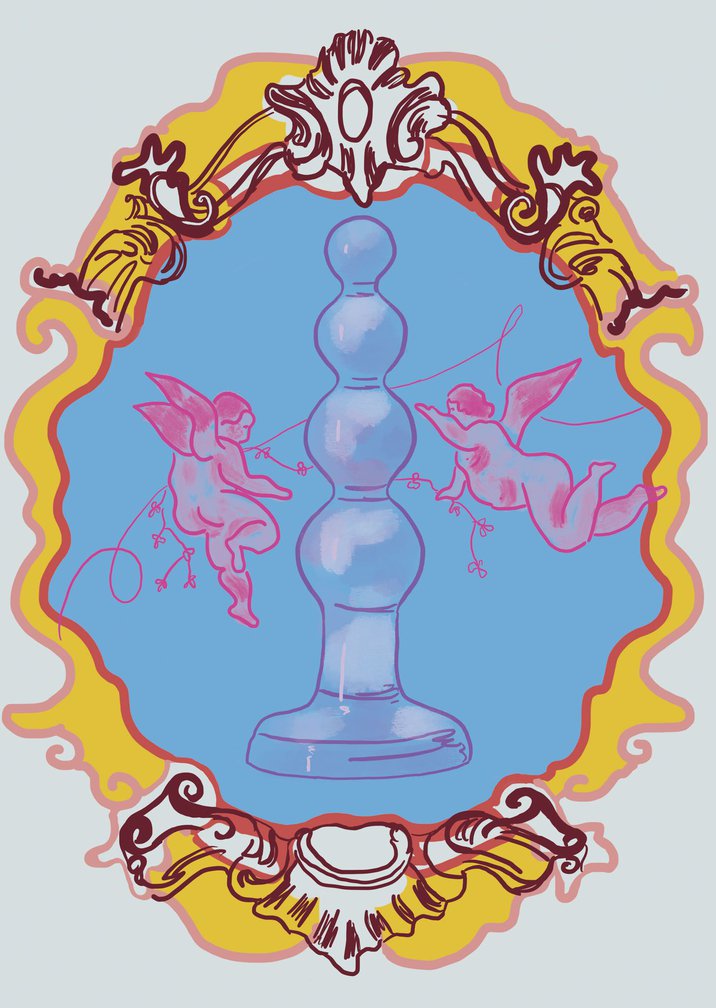

Artiq Can you tell us a bit more about the inspiration and creative process behind Apparition of a Sacred Vessel, the work you've created for this year's exhibition?

Louise Sex toys have been a recurring motif in my work for a while because I think their materials and shapes are really sculptural and sensually engaging, but they also have this weight of association, despite being often quite perversely childish plastic toy objects. In my broader investigation of Catholic imagery and visual language, you see instruments of pain, and martyrdom that result in rapture and bliss.

The dialogue between the conservative and the kinky is very broad. When you have a torture device like a whip, versus something designed to thrill, I think you capture something so much greater about people and desire: the tension between the human desire to believe but also to experience. Ultimately the end game is pleasure, whether eternally in heaven or in that moment of gratification.

Apparition of a Sacred Vessel is the presentation of that object of ‘earthly desire’ in a divine realm. I’ve been looking at church and chapel architecture where every shape, figure and form in the sacred space was loaded with emotional, manipulative impact to keep the followers faithful. Playfully challenging the seriousness of the Church's teaching, I question whether all of this still has a place, or if something more true or real can appear by subverting things we already 'understand'.

Louise Sex toys have been a recurring motif in my work for a while because I think their materials and shapes are really sculptural and sensually engaging, but they also have this weight of association, despite being often quite perversely childish plastic toy objects. In my broader investigation of Catholic imagery and visual language, you see instruments of pain, and martyrdom that result in rapture and bliss.

The dialogue between the conservative and the kinky is very broad. When you have a torture device like a whip, versus something designed to thrill, I think you capture something so much greater about people and desire: the tension between the human desire to believe but also to experience. Ultimately the end game is pleasure, whether eternally in heaven or in that moment of gratification.

Apparition of a Sacred Vessel is the presentation of that object of ‘earthly desire’ in a divine realm. I’ve been looking at church and chapel architecture where every shape, figure and form in the sacred space was loaded with emotional, manipulative impact to keep the followers faithful. Playfully challenging the seriousness of the Church's teaching, I question whether all of this still has a place, or if something more true or real can appear by subverting things we already 'understand'.

Artiq How does Christian mythology become an efficient tool to narrate the stories of contemporary queer culture?

Louise The stories we tell within religion, Christian or otherwise, are full of transformation and miracles. To me, queer culture centres on freedom and fluidity, and a visual language that aims to amplify faith and belief in a world where angels appear with divine news, or saints perform miraculous cures and apparitions, is well suited to contemporary stories that are not constrained to repressed histories.

The contradiction of the Church being the source of a lot of this repressed history only makes it a more interesting space to explore and subvert. There's already an existing tradition of reclamation of power through bestowing new meanings on old ideas, with various icons of Christian history being repurposed within the queer culture.

Saint Sebastian for example, who features in the stained glass panel that is being exhibited, is traditionally favoured by artists as a figure on whom to display prodigious skill at painting homoerotic musculature, on account of being shot by arrows shirtless and tied to a post, and somewhere along the line hit cult status as a sex symbol.

Louise The stories we tell within religion, Christian or otherwise, are full of transformation and miracles. To me, queer culture centres on freedom and fluidity, and a visual language that aims to amplify faith and belief in a world where angels appear with divine news, or saints perform miraculous cures and apparitions, is well suited to contemporary stories that are not constrained to repressed histories.

The contradiction of the Church being the source of a lot of this repressed history only makes it a more interesting space to explore and subvert. There's already an existing tradition of reclamation of power through bestowing new meanings on old ideas, with various icons of Christian history being repurposed within the queer culture.

Saint Sebastian for example, who features in the stained glass panel that is being exhibited, is traditionally favoured by artists as a figure on whom to display prodigious skill at painting homoerotic musculature, on account of being shot by arrows shirtless and tied to a post, and somewhere along the line hit cult status as a sex symbol.

Louise Benton for Queer Frontiers

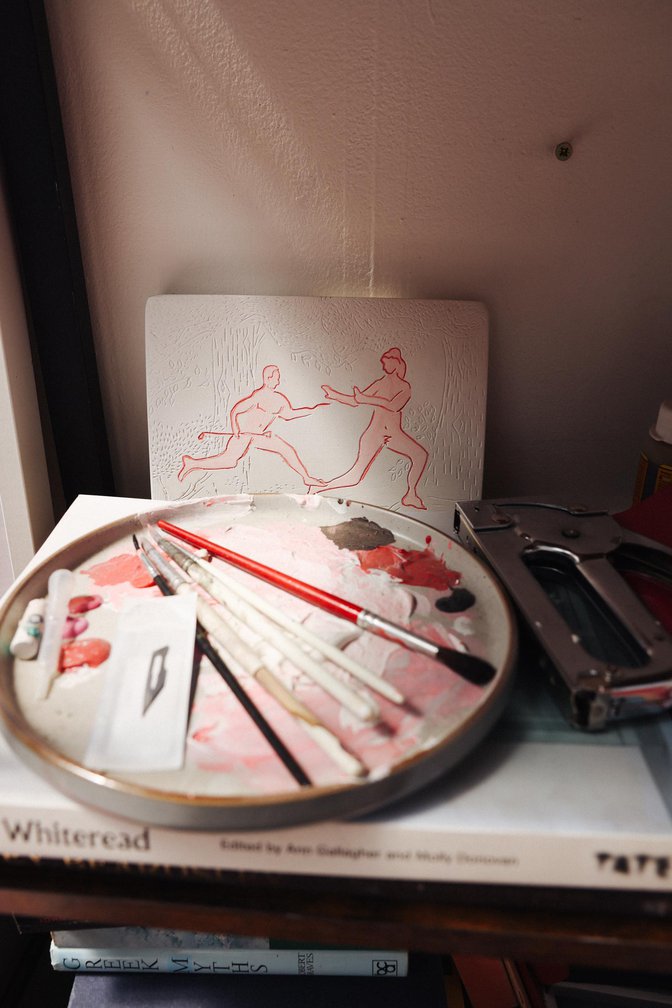

Artiq You work with a multitude of media. Is the medium itself an inspiration for your visual stories?

Louise Material can often hold as much significance as subject, and what better way to deconstruct our structures of worship than to reform the stone, clay, glass and metals that built it? When we see stained glass for example, regardless of what it depicts, we are immediately placed within a church context.

I like the idea that the viewer is given cause to reassess their immediate associations when they get closer and look at the work, hopefully coming away with something more truthful or relevant to them. On a purely personal level, exploring and learning new materials and techniques is one of the most exciting parts of my process.

Louise Benton is exhibiting in Queer Frontiers: Queer Myths, Queer Futures

June 29 - July 4 at 1-4 Walker's Court, London W1F 0BS.

Louise Material can often hold as much significance as subject, and what better way to deconstruct our structures of worship than to reform the stone, clay, glass and metals that built it? When we see stained glass for example, regardless of what it depicts, we are immediately placed within a church context.

I like the idea that the viewer is given cause to reassess their immediate associations when they get closer and look at the work, hopefully coming away with something more truthful or relevant to them. On a purely personal level, exploring and learning new materials and techniques is one of the most exciting parts of my process.

Louise Benton is exhibiting in Queer Frontiers: Queer Myths, Queer Futures

June 29 - July 4 at 1-4 Walker's Court, London W1F 0BS.